Several variables dictate the number and types of records you may find inside pension files. These variables include the following:

- The original filing date.

- The person who originally filed for the pension.

- The outcomes of the filing.

THE ORIGINAL FILING DATE

As I have seen numerous Civil War pensions over the years, I have discovered that there are certain elements that are consistent based upon when the pensions were filed.Wartime Pensions

Veterans’ pensions that were filed during the Civil War tended to have less documentation than later pension applications. If the unit was still in the field, it was relatively easy for the claimant to have a commanding officer provide documentation of the nature of the soldier’s wound or death. Often this documentation was the deciding factor whether a soldier, sailor, or marine qualified for a pension based upon injury or if a serviceman's death was war related.The value of the wartime pensions include descriptions of the events that were close to the time of occurrence. Later pensions often require more documentation. The proliferation of accounts may have several accounts that conflict with one another and may not be correctly remembered twenty years after the fact. In addition, those who may have better testimony of the event may be difficult to find or may even be dead in the years following the war.

Unless it is a dependent’s pension, there probably will not be too many references of genealogical importance as it will not be necessary for the soldier to file information regarding his family. That does not mean you shouldn’t seek out these pensions, as surprises can be found in any record.

One such widow’s pension record yielded church membership information that directly conflicted with published histories about the soldier. At least five published volumes reported (and several emphatically) that the soldier in question was a Quaker pacifist; however, pension records indicated that he was actually Lutheran. Records from the local Lutheran congregation confirmed and documented that he was raised as such from the time of birth and was active as a Lutheran throughout his early life.

Unlike others in his father's family, he was never a Quaker. This assumption grows stronger with each published account of his life. The earliest account has him living with his uncle and attending a Quaker school - this not only was possible, but probable as well. From this early reference, others have the soldier standing in front a of Friends Meeting renouncing his faith so he might go to the battlefield. Although it is a great piece of literary characterization and hyperbole, it is also a work of fiction as it is far from the truth.

Post War Applications Filed under the General Act prior to 1891

These pension files tend to be the most complete records, as documentation was critical in establishing an applicant’s eligibility. In addition, if the veteran was married and had dependent children – this information was often provided in the event that a pensioner died and his widow or dependent children were eligible to apply for dependent pension.The documentation of the wound or illness will provide testimony of relatives, friends, and fellow veterans. In some cases, insight to a person and his family becomes evident. In one post-war pension, the soldier's brother-in-law did not help his sister's cause in obtaining a widow's pension as her brother basically indicated that the former soldier's death was due in part to heavy alcohol abuse.

You may also learn of prior marriages, names of the veteran’s parents, documentation of marriages, documentation of the birth (and death) of children, where the veteran lived since the war, and other various sundry items of interest. The diagnosis and treatment of said wound or ailment will be documented by physicians and the veteran’s vital signs are often recorded. Since these are submitted when an increase in pension benefits were sought, you can find a time line of the veteran’s health over the years.

Some of these records may indicate a person's service in another conflict. I have seen detailed accounts of one soldier's involvement in the Mormon War, documentation of a wound that occurred in the Bleeding Kansas border struggle, several Mexican War references, foreign service before the soldier immigrated to the US (most of these were in the armies of various states), and one Civil War pension that was merged with a Spanish-American War claim in the early 1900s.

Applications under the Act of 1890

These applications were originally sought for a post-war disability. Some of these files can be quite large and may encompass two file folders. Like the post war files, you will find much of the same documentation that you find under the post-war General Act applications. The difference will be the documentation of the wound or ailment that prevents the veteran from earning a living by manual labor will not be related to a service injury.

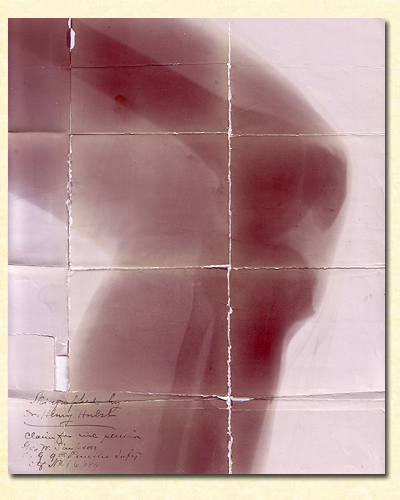

Rudimentary Radiograph from 1902 used as evidence in a pension claim

The Age/Service Acts

Those pensions filed for age related benefits will be smaller than the other post-war pension applications. There were a number of forms that were required including documentation of age and information regarding dependents. Since these are not related to illnesses or injuries, documentation from others will not be generally found. The only time when you find documents from others is when the soldier’s age is in question and/or to document a date of the veteran’s marriage. These pensions are not contained in envelopes, as older files, but rather are attached to a fastener file.

Fastener file used for pensions filed under the age/service acts.

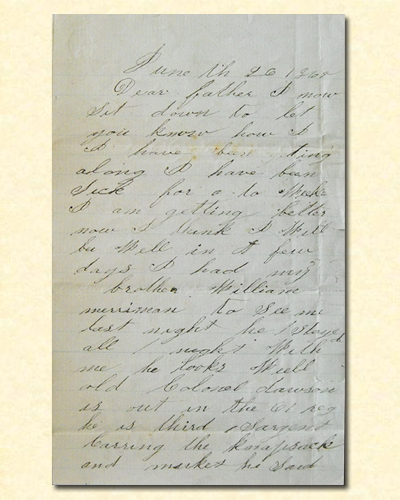

THE PERSON WHO FILED THE ORIGINAL CLAIM

When the person filing for the pension was other than the veteran, the files become more interesting. The most interesting are when parents file for their son’s pension. Because a parent had to prove that his or her son had materially contributed to the family's substance, parents would often provide wartime letters from their sons that referenced their monetary help to the family. I have found these letters fascinating. In some pension files, you may find upwards of twenty letters that the parent parted with in order to be provided for in his or her old age.Letter to parents from the field used as evidence of their son's support

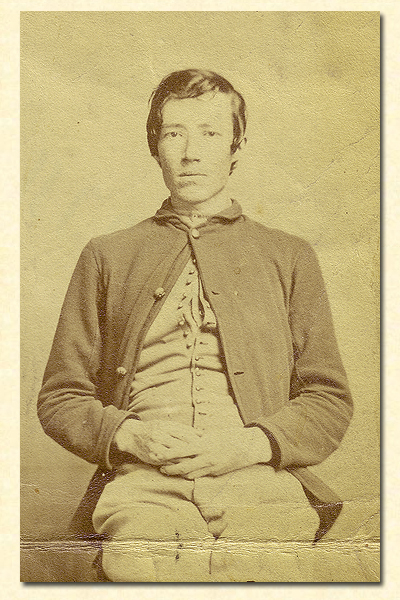

Widows and dependent children pensions usually will provide documentation of the marriage and birth of the children. In some cases the actual wedding certificate is provided. In about four pensions that I've viewed, a photo of the soldier was included as part of the documentation. Since many of these files may not have been accessed for over 100 years, the photos are in excellent shape and a good scan of the photo can provide with an excellent “likeness” of the soldier in question.

Photo of a soldier sent in by his father as pension evidence

THE OUTCOMES OF THE FILING

Even if a pension was not successful, these incomplete files should provide documentation of age, marriage, and children may be listed. Veterans may be denied pensions for a variety of reasons. Some of these could be that the soldier filed under an act that he was not eligible; the soldier was mustered into state service, but not into federal service – so he was not qualified to receive a pension; the soldier was a deserter; or the soldier died shortly after filing and the claim was considered abandoned.For widows, claims may have been rejected because the claimant was divorced from the veteran; the widow had remarried; the soldier had not been honorably discharged, a completing claim from another wife had been approved and this wife had been considered the legal heir of the veteran; and occasionally a widow was rejected as the soldier’s marriage late in life was considered suspect. In the latter category, I saw a pension where a soldier married a young girl in 1912. Upon his death in 1913, the town’s postmaster petitioned the pension office to deny her widow’s claim, as the marriage, while legal, appeared to be suspicious in nature.

For dependent children, the pensions usually were rejected on the basis that the child was no longer a minor. While orphaned siblings could file for their brother’s pension, these recipients had to be of minority age. In one pension I studied, a child was determined to be not the soldier’s child as he had been imprisoned at the estimated time of the child’s conception. It was impossible for him to be the father of this child.

A parent’s claims for a soldier’s pension were usually rejected because there was inadequate documentation presented to prove that the soldier materially provided for their living. Step-parents were also ineligible to apply for a parental dependent pension even if the step-son provided for his step-parent’s living.

A soldier’s claim under the Service Acts may have been rejected as the soldier counted service under the state’s jurisdiction. While his entire service may have been over three years in length, his federal service was actually less than this period. Three years of service were required for full service related benefits. Likewise, a soldier who was a deserter (even when charges were forgiven) was not allowed to count time during which he was AWOL.

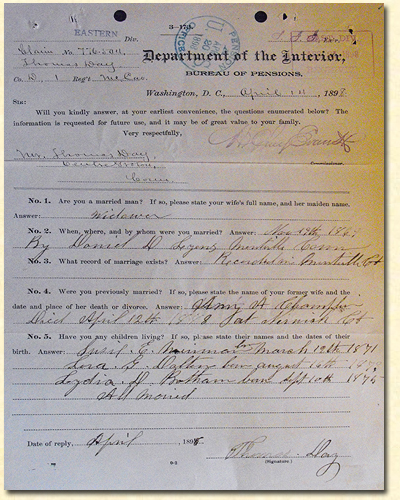

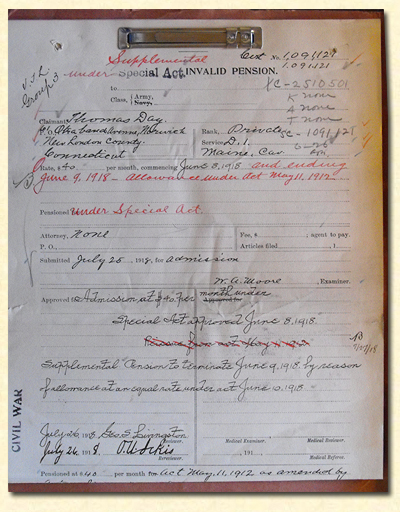

WHAT PENSION RECORDS TOLD ME

While I have studied over 500 pension records, only four of these were for my direct ancestors that included three great-great grandfathers and one great grandfather. While all four ancestors’ pensions provided a wealth of data, the most valuable was for my great grandfather, Thomas Wesley Day.For years, I hit a brick wall regarding my great-grandmother. I was always told that her name was Alice Amy Champlain; however, I never could find any record of her or her family. When I looked at her husband’s pension record for the first time over 11 years ago, I found that I had been misinformed of her name.

Her last name was not Champlain, but rather Champlin. In addition, family tradition had transposed her first and middle names. The pension records indicated that her name was Amy A. Champlin. I additionally learned her date of death and the birth dates of her three children.

Questions answered by claimant concerning his family

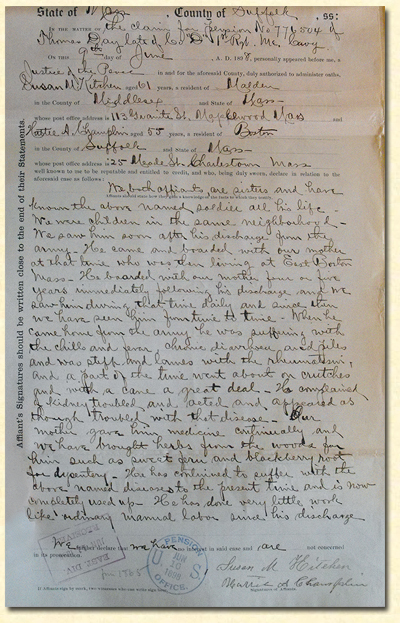

Other information came to light regarding this ancestor such as the date and location of his marriage. Additionally, I always wondered how my great-grandfather from Maine and his wife from Connecticut met. This becomes evident by reading the documentation that was provided by others. By comparing with other research, the two sisters who were neighbors of my great grandfather in Maine told of how he stayed with their mother following the war. At some point, she moved to Massachusetts with her two daughters and both daughters married men they had met in the Boston area. One of the sisters was married to Alfred Champlin who had moved to Massachusetts from Connecticut. Alfred was the oldest brother of my future great-grandmother - the rest is history.

Affidavit of the two sisters who knew

Thomas Day from his childhood.

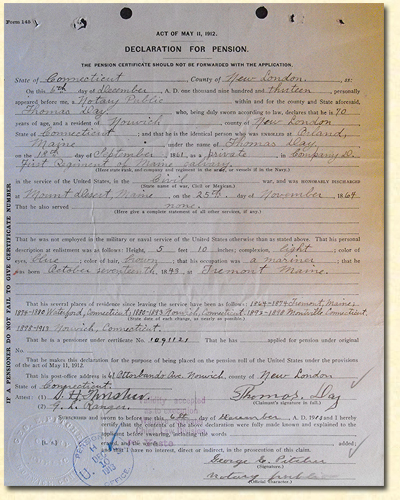

I also learned some descriptive info about this ancestor. Like me, he had blue eyes. There is the possibility that I inherited this trait from him.

Declaration by pensioner that features a physical description

Although my great-grandfather’s second marriage was not documented in the pension, his future wife was often utilized as a witness as she served as his caretaker prior to their marriage. The pension record documented his middle name of Wesley which is found in no other records.

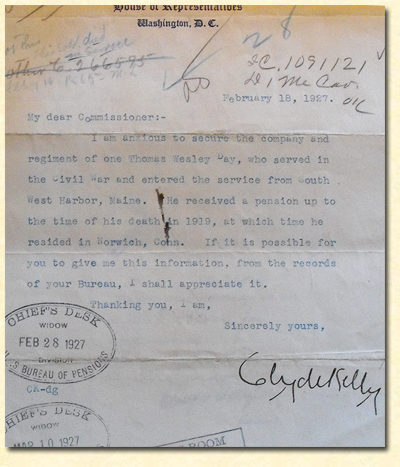

Letter from my grandmother's Congressman

that mentions Thomas Day's middle name

This particular Civil War pension opened up several research doors for me and allowed me to discover more about my great-grandmother’s family. For other relatives, pension records provided much needed information to help understand illnesses, occupations, and genetics.

Not all pension records lead to stories of heroism and not all Civil War vets were upstanding men. In my Civil War research, I discovered substance abusers, men who inflicted injuries upon themselves for the purpose of being discharged, one man who murdered his own brother, six suicides, husbands who deserted their wives, three individuals who changed their names to escape their pasts, an alarming number of divorces, and one medal of honor winner who spent more time deserting and defrauding the federal government than he did in actually serving his country. Even the stories of infamy might provide a narrative that will enliven your family history.