Ask any genealogist to list his or her frustrations and inevitably the term “brick wall” will surface in the discussions. Brick walls are points when all clues regarding an individual are seemingly non-existent. In most cases, these brick walls occur as we go backwards in our lineage and we reach a point where an ancestor’s identity is unknown.

For Americans, this can happen within a few generations as

record keeping was sparse, spotty, or non-existent in some locales during the 19th

century. Municipalities, counties, and

states had varying degrees of public record keeping. In other words, there is

no official US standard and American genealogy can be difficult at best.

When we begin our genealogical quest, our mission of

discovering each ancestor is actually a series of brick walls that will be

either knocked down with extensive research or will remain solid. Sometimes this happens with one piece of

direct evidence, or it only occurs with constant chiseling with indirect

documentary or DNA evidence (see example).

Not only will we encounter brick walls while seeking our direct ancestors,

but we will also run headlong into the same barriers when we trace the descendents

of those ancestors as well – our collateral lines.

One of My Walls

For 37 years, I’ve been searching for my great-grandfather’s

sister with very little luck. Over time, I've been able to ascertain that Frances Jenett Owston was born

in Allegheny City (now Pittsburgh’s North Side), Pennsylvania in 1852, but I never could find her as an adult. I first became aware of her existence in early 1978 when

my great-grandparents’ family bible surfaced after being out of the bloodline

for nearly 50 years. Between the pages

of this large presentation bible was a piece of heavy paper stock with 11

locks of hair; each one was identified and dated.

Some individuals had two samples from different periods of

their lives including my great-grandfather who had one dated from 1858 when he

was four years old and one from twenty-two years later. While most of the names were easily

identifiable as being members of my great-grandparents’ household, two were

not. One was a Grandma Ritchey, 70 years of age – who

was eventually determined to be my third great grandmother. The other was for Fannie Owston; her sample

was dated 1859.

For 27 years, I had assumed that this was my

great-grandfather’s first cousin, Frances W. Owston, who also lived in

Pittsburgh. Since my great-grandfather’s

family was musical and this Fannie Owston was a music teacher, it seemed

plausible. Confirming the identification

was problematic, as I couldn’t initially find my second great-grandparents in

the 1860 census. Despite repeated searching of the census records,

I was unable to find their listing until 2006. The problem was that the family was

listed under an incorrect but similar surname and the head of the house’s (my second great-grandfather) initials were

transposed. See my post on this.

Although finding the census in 2006 provided additional evidence of her existence

as my great-grandfather’s sister, I was able to determine the identity of Fannie Owston four years earlier. While browsing through the genealogical books in the Carnegie

Public Library in Pittsburgh, I found Ken McFarland’s book Births,

Marriages, and Deaths of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania 1852-1854. McFarland’s a diligent researcher who has transcribed

and indexed numerous records from the Greater Pittsburgh area.

While in 1980 I had previously looked at the microfilm of

Allegheny County’s records from this period, I found no one in our family listed

and never revisited these documents.

This time, however, I was interested in McFarland’s book, not for my own

family, but for siblings of 1200 Pennsylvania Civil War soldiers that I am

tracing from womb to the tomb. I was

hoping to find maiden names of the mothers of some of these soldiers.

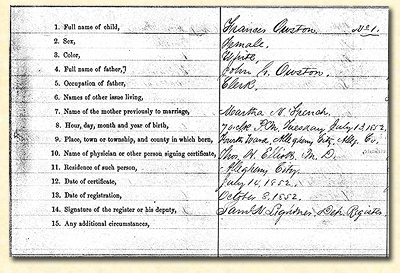

As I opened the book, there it was on page one – and

it was even registration number one: the birth record of Frances Owston daughter of John G. Owston

and Martha N. French. She was born at 7

PM on July 13, 1852 in the fourth ward of Allegheny City, PA. Since this time, I’ve searched diligently for

Frances Owston, but outside of the additional listing in the 1860 census, I’ve

had no luck.

The family had moved from Pittsburgh to Canada in about 1857

and was in Detroit in 1860 where my second great-grandmother died that same

year. In 1995, I had traveled to Detroit

to research my second great grandparents.

While I found some information on the family, nothing on Frances

surfaced. No one else was buried in the

plot where my second great grandmother was buried, so it seemed plausible that Fannie survived the family’s eight year stay in Michigan.

By 2009, I became aware of my family’s 1863 move from

Detroit to East Saginaw along with my second great-grandfather’s marriage to

and subsequent divorce from Permelia Condon.

This heretofore unknown tidbit was a serendipitous discovery through searching

my surname in Google Books. A published biography

and photo of my second great-grandfather with information about his work in Saginaw

led to the discovery of his second wife.

After the couple separated, the family moved back to Allegheny City in

1868.

Unfortunately, Detroit, East Saginaw, and Wayne and Saginaw

counties were not registering vital information during the 1860s and

1870s. If Fannie had moved back to

Allegheny County with her father and brother, chances of finding her if she

married or died were marginal. Allegheny

County did not begin registrations of marriages until September 1885 and

Allegheny City did not register births or deaths until July 1882. I had already

checked all of these records in the past for anyone with my surname. If death or marriage occurred before the

1880s, I might never find her. But, I

never stopped searching.

Background on the Records

While Pennsylvania is currently ranked at sixth in

population, it was the second most populous state for much of its history. You would think that a vital “keystone” of a

state might have policies in place to register births, marriages, and deaths –

but alas, it did not for many years. In

the mid 19th century, Pennsylvania attempted to institute registrations

of births, marriages, and deaths. This

1852 registration was unsuccessful, and the state dropped the experiment after two

years.

One problem was that registration was not compulsory and many

individuals failed to comply. Frances

Owston was the first to be registered in Pennsylvania’s second largest county

and third largest city, but her birth occurred seven months after the law was

effected and was not registered by the physician until three months later. Her brother’s birth two years later in the same town was never registered with

the state.

Eventually, individual municipalities began to register

births and deaths over the next 50 years. Pittsburgh, the second largest city in the Commonwealth, began in 1870. As previously

stated, Pittsburgh’s neighbor to the north, Allegheny City, waited 12 more

years to register birth and death records.

Other towns followed suit but only when it was convenient to do so.

Additionally, none of these registrations through 1905 were

mandatory. A case in point is my

father’s siblings. All five were born before 1906 and two died in early childhood

during the same period; none of these events were registered even though the municipalities were actively registering births and deaths.

The practice with marriages and divorces in Pennsylvania was

different. As of September 30, 1885,

Pennsylvania required that all counties register marriages and these be on file

in the local county courthouse. Marriage

registration was mandatory and the same process exists today. Divorce records were registered with the

county’s Prothonotary beginning in 1804.

Statewide mandatory vital registration, however, did not begin until

1906, which is late considering the population of Pennsylvania and that it prides

itself on being the second state to ratify the Constitution.

Fast forward

After November 2014’s election, Governor Tom Corbett may not

think he has a friend in Pennsylvania, but he certainly has a friend in me, as

he signed Act 110 (Pennsylvania Vital Records Bill SB-361) into law on December

15, 2011. I was one of the many people to sign several petitions over the last

10 years to hasten the Commonwealth to begin this process. The bill went into effect on February 13, 2012

and the Division of Vital Records transferred all death certificates 50 years

old and older and birth certificates 105 years old and older to the

Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg.

Declaring these documents as old records made them easily available to the public and the old paper indexes for both became listed on the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s website. The indices, however, are PDF scans of the typewritten copies and are laborious to use – but, at least, they are there. Copies of the original records are now available to anyone through the State Archives for $5.00. This is providing you have the registration number from the indices. From my personal experience, the turnaround of the processing takes less than a week.

Declaring these documents as old records made them easily available to the public and the old paper indexes for both became listed on the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s website. The indices, however, are PDF scans of the typewritten copies and are laborious to use – but, at least, they are there. Copies of the original records are now available to anyone through the State Archives for $5.00. This is providing you have the registration number from the indices. From my personal experience, the turnaround of the processing takes less than a week.

How important is this move?

Being a native Pennsylvanian and an avid researcher of Pennsylvania

records, this was a dream come true. In

the past, Vital Records’ processing was slow (up to a month); they could reject

you if you were not a blood descendent or legal representative of the person on

the birth certificate (a caveat on their forms); you were not allowed to copy,

photograph, or publish an image of the record; and the service was expensive to

use, especially if you simultaneously wanted numerous certificates. Prior to

the transfer, a death record would cost $10, unless you didn’t know the date

and then an additional search fee was of $10 was charged for a search of ten

years.

While looking for my great-grandfather’s first cousin’s

death record, I got stung for $50. Not knowing the date of his passing, I

ordered a copy of the certificate with a 10 year window (1920-1929) search –

that was $20. No document was found. I

ordered another search at $20 for the years of 1910-1919. This was also

inconclusive. Several years later while

perusing a church’s records on site, I found his 1923 burial date – the

cemetery provided an exact date of death.

I ordered the certificate again ($10) with the exact date and received

it. Unfortunately, Vital Records did a

sloppy job on the first search and I was out $30.

Further Movement

In August 2012, the Pennsylvania State Archives and Ancestry

signed an agreement for the company to digitize and upload the records. These would be freely available to Pennsylvania

residents if they register at http://www.portal.state.pa.us/. All Ancestry customers would also have access

as part of their individual memberships.

On April 18, 2014, Ancestry announced that it had uploaded

the images and database information on death records from 1906-1924. As with many individuals, I began searching

for family and others. As with the

database and the certificates, there were some issues that I will address in

future posts. The second group,

1925-1944, went live on June 24, 2014.

The records through 1963 completed the death certificate process on

October 24, 2014.

Birth certificates for 1906 will be completed in March

2015. No timeline has been communicated

regarding the records for 1907-1909.

Until the end of this year, only the indices for 1906-1908 are currently

available.

Brick Wall Smashed

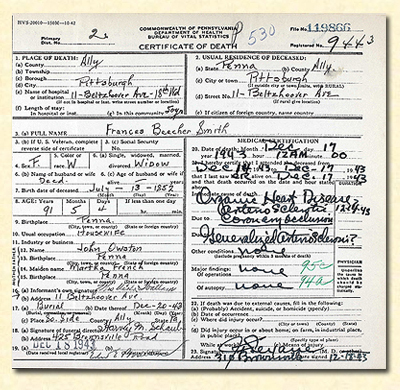

In July 2014, I decided to see if Ancestry had completed any

further uploading of death certificates.

They had, and I did my customary search of my surname. To my surprise, I found a Frances Beecher

Smith who was the daughter of John Owston and Martha French. This was my great-grandfather’s missing

sister.

After doing additional research in Pittsburgh, I began to

piece together her story: two failed

marriages, a bitter rivalry with another woman, the birth of two children, the loss of a

grandchild, and the finding of another.

While she never owned her own home, what she did have was far more

precious than gold. She lived a long

life and had the support of a family that dearly loved her and to whom she

reciprocated that love.

My biggest surprise about Fannie was that she lived less

than 15 miles from my childhood home. Outside

of the records I previously mentioned, I had never encountered her in any other until

now. In fact, I had walked across her

grave (which is unmarked) on at least four occasions looking for others in the

same cemetery. No stone is present, and

even if there was one, I wouldn’t have recognized the name Frances Smith.

In addition, I have found Fannie’s only surviving

great-grandchild who lived in the same home with her for two decades. We have corresponded and talked on the phone

concerning the differences and similarities in our respective families. In addition, this third cousin turns out to

be a double third cousin as I am related to both her maternal

grandparents. We still have a lot of

catching up to do yet.

Thanks to the 48 members of the Pennsylvania Senate and 194 members of Pennsylvania House of Representatives who voted to pass this act, to Governor Tom Corbett who signed the bill into law, and to the forward thinking folks at the Pennsylvania State Archives and Ancestry for collaborating on this important project.

I have already viewed several hundreds of these certificates

and in our next installment I will deal with death records, primarily those from

Pennsylvania, and their importance as genealogical evidence and the inherent

problems regarding these records as sources of information.

References

Ancestry.com. (2014). Pennsylvania, Births, 1852-1854. Database available

at http://www.ancestry.com

Ancestry.com. (2014). Pennsylvania, Death

Certificates, 1906-1963. Database available at

http://www.ancestry.com

Gruber, T. (2014). People for Better Pennsylvania Historical Records Access (PaHR-Access):

Frequently Asked Questions. http://users.rcn.com/pahraccess/PaHR-Access-FAQ.htm

Gruber, T. (2014). People for Better Pennsylvania Historical Records Access (PaHR-Access):

Genealogists, Researchers, Family Historians. http://users.rcn.com/pahraccess/PaHR-Access.htm

McFarland, K.T.H. (1999). Births, Marriages, and

Deaths of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania 1852-1854. Apollo, PA:

Closson Press.

Pennsylvania Department of Health. (2014). Act 110

– Public Records (formerly known as Senate Bill 361). http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/public_records/20686

Pennsylvania General Assembly. (2012). Senate Bill

361; Session 2011-2012. http://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/billinfo/bill_history.cfm?syear=2011&sind=0&body=S&type=B&bn=361

Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. (2014). Vital Statistics Records at the Pennsylvania State Archives. http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/genealogy/3183/vital_statistics/387291